Tokyo-some-komon

Getting it right is not easy.

That’s what makes it interesting.

“Komon”(Fine-pattern dyeing) is a type of pattern for stencil dyeing, and just as the name implies, it uses very finely detailed patterns. The art of fine-pattern dyeing was first used for kamishimo worn by samurai during the Edo Period, but evolved into many different playful patterns among the townsfolk of Edo. Yukio Ishizuka, 4th generation owner of Ishizuka Senko, brings the old-fashioned fine-pattern dyeing to the modern day.

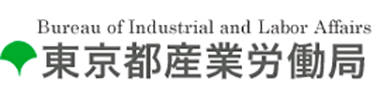

Yukio Senko engaged in stenciling work. Stenciling paper must be moved dozens of times in order to paste one bolt of cloth. Matching up the seams of the pattern is no easy task either.

Yukio Senko engaged in stenciling work. Stenciling paper must be moved dozens of times in order to paste one bolt of cloth. Matching up the seams of the pattern is no easy task either.

Ishizuka Senko, founded in 1890, has a history stretching back for over a century, but it was not until Yukio Ishizuka’s generation that they started doing fine-pattern dyeing. Kimono, which people once wore on a daily basis, are now expensive articles of clothing. As such, people became more particular about the pattern, and demand shifted from medium fine-pattern dyeing to elaborate fine-pattern dyeing, which requires more refined techniques. However, advanced skills were needed in order to dye patterns so delicate that they look like plain cloth at first. Yukio Ishizuka tells us “Detailed patterns really show the skill of a craftsmen, and you can’t take any shortcuts. No craftsmen in our workshop did extremely detailed Edo-some-komon, and there were few people who could even teach those techniques. I visited other workshops to speak with them, get them to show me their work, practiced through trial and error, and did difficult jobs day in and day out in order to learn these skills.

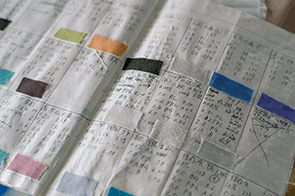

In dyeing work, the process that demands the most of craftsman skills are is stenciling. Stenciling is the process of placing stencils on the fabric and applying dye resistant paste with spatula-like tool called a koma. The part with dye resistant paste applied is not dyed to the ground color, but remains white and appears as the design, so how well the craftsman can apply this paste determines the quality of the dyeing.

“Stenciling is such delicate work that even the quality of wood used in a koma can affect the quality of the dyeing. That’s because the quality of the wood affects the whip of the koma. I also sand the tip of my komas so that I can spread paste evenly, and how I sharpen komas can also affect the finished product. Depending on the stencil and pattern, I also adjust the hardness and the adhesiveness of the paste. Weather on the day of work also affects the work. It takes a lot of experience and effort in order to spread paste evenly along the stencil.” True craftsmanship makes quality, even when work conditions change.

When we asked why Mr. Ishizuka finds manual work interesting, he smiled and told us that you can’t make a good product unless all the conditions are just right. The pleasure of making something just as you imagined it must special indeed.

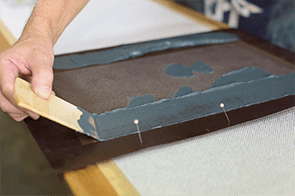

Good stencils are essential for making good fine-patterns. Ise stencils, a traditional craft tool made with Mino Japanese paper, are used to make Edo fine-patterns. The elaborate and beautiful hand-carved patterns are created by stencil makers are a sight to behold. Mr. Ishizuka has also been asked to dye samples of stencils by the Ise Stencil Technique Preservation Society. “You cannot dye a good product without a good stencil. In order to leave this traditional craft for the next generation, it is important that we not only train successors, but also secure the right tools and create the right environment for making good dyed products. I hope to continue my exchanges with Ise stencil craftsmen in order to keep the skills of fine-pattern dyeing alive.”

With modern technology, it is probably easy to do the same fine-pattern dyeing. But dyed products made by hand have a unique warmth to them. Each and every one has its own expression. Mr. Ishizuka will be in his workshop again today in order to convey that charm to as many people as he can.

Tokyo –some-komon Master of Traditional Crafts

石塚幸生 Yukio IshizukaMr. Ishizuka was born in Tokyo in 1948. He is the 4th generation owner of Ishizuka Senko, founded in 1890. In 1968, he started work as a dyeing craftsman. In 1995 he was certified as a Master of Traditional Crafts and in 2002 he was certified as a Tokyo Meister. He has won many prizes, including the Prime Minister’s Award at the Traditional Craft Products Open Call Exhibition in 2000. He also received the Order of the Sacred Treasure in 2016. Mr. Ishizuka serves as the Vice Chairman of the Tokyo Dyeing Industry Cooperative Association.

Ishizuka Senko Limited

1-16-1 Motoyokoyama-cho, Hachioji-shi, Tokyo

TEL: 042-642-4400

Hours: 08:00 – 17:00 (Closed Saturdays, Sundays, and public holidays)

http://tokyokomon.jp

Yukio Senko engaged in stenciling work. Stenciling paper must be moved dozens of times in order to paste one bolt of cloth. Matching up the seams of the pattern is no easy task either.

Yukio Senko engaged in stenciling work. Stenciling paper must be moved dozens of times in order to paste one bolt of cloth. Matching up the seams of the pattern is no easy task either.